How Food Impacts Your Biological Age: Added Sugar Speeds Up Epigenetic Aging, While a Nutrient-Rich Diet Can Slow It Down

A new study reveals the surprising link between diet and epigenetic aging. Learn how consuming added sugar can accelerate biological aging, while a nutrient-rich diet can help slow it down. Discover the power of food in shaping your overall health and longevity.

DR ANITA JAMWAL MS

9/3/20248 min read

The study published in JAMA Network Open, explored the relationship between diet, nutrient intake, and epigenetic aging. It found that higher intake of essential nutrients was associated with a younger epigenetic age, while higher added sugar intake was associated with an older epigenetic age. The study also found that following a Mediterranean diet was associated with a younger epigenetic age. These findings suggest that diet plays a crucial role in modulating epigenetic aging and that promoting healthy eating habits may be an effective strategy for promoting healthy aging.

Key points

Epigenetic aging refers to changes in gene expression patterns that occur as we age.

Epigenetic clocks can predict biological age more accurately than chronological age.

A recent study examined the relationship between diet, nutrient intake, and epigenetic aging in midlife women.

Added sugar intake was found to be associated with an older epigenetic age.

Higher intakes of essential nutrients were associated with a younger epigenetic age.

Following a Mediterranean diet was also associated with a younger epigenetic age.

Exploring the Relationship Between Diet, Nutrient Intake, and Epigenetic Aging:

Epigenetics, a field that examines how genes are turned on or off without altering the underlying DNA sequence, has gained significant attention in recent years. One of the most compelling areas of study within epigenetics is the concept of "epigenetic aging," which refers to changes in gene expression patterns that occur as we age. These changes are often reflected in what are known as epigenetic clocks—biomarkers that can predict biological age more accurately than chronological age. Recently, a cross-sectional study involving 342 Black and White women at midlife has shed new light on the relationship between diet, nutrient intake, and epigenetic aging. This blog post delves into the key findings of the study, exploring how dietary patterns, including essential nutrients and added sugar intakes, impact epigenetic aging.

The Importance of Epigenetic Aging

Before diving into the study, it's essential to understand why epigenetic aging is crucial. Unlike chronological age, which simply counts the number of years a person has lived, biological age reflects the actual condition of the body's cells and tissues. Epigenetic clocks, like the GrimAge2 clock used in this study, provide a way to measure this biological age by analyzing specific DNA methylation patterns. These clocks have been shown to predict health outcomes, including mortality and morbidity, more effectively than chronological age. Therefore, understanding what factors influence epigenetic aging could lead to new strategies for promoting healthy aging and preventing age-related diseases.

Study Overview: Diet and Epigenetic Aging

The study in question analyzed dietary patterns, nutrient intakes, and their association with epigenetic aging in a diverse cohort of midlife Black and White women. The researchers focused on several key dietary factors:

Added Sugar Intake: The study looked at the mean daily intake of added sugars, which are sugars added to foods during processing or preparation.

Essential Nutrients: The intake of essential nutrients, particularly those with known epigenetic properties, was assessed.

Diet Quality Scores: The study used established diet quality indices like the Alternate Mediterranean Diet (aMED) and the Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI)–2010 to evaluate overall diet quality.

Epigenetic Nutrient Index (ENI): A novel index developed for the study, the ENI, was designed to reflect nutrient intakes that theoretically support epigenetic health.

The primary outcome measured was GrimAge2, a second-generation epigenetic clock that uses DNA methylation data to estimate biological age. The study's main objective was to determine whether higher intakes of essential, pro-epigenetic nutrients and adherence to high-quality diets were associated with a younger epigenetic age, while higher added sugar intake was hypothesized to be associated with an older epigenetic age.

Key Findings: Sugar and Epigenetic Aging

One of the most striking findings of the study was the association between added sugar intake and older epigenetic age. The researchers found that each gram increase in added sugar intake was associated with a 0.02-year increase in GrimAge2, indicating that higher sugar consumption may accelerate epigenetic aging. This finding aligns with existing research linking high sugar intake to various health issues, including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases, which are often associated with accelerated aging.

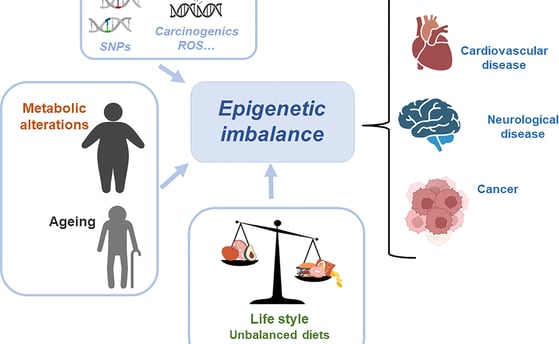

The biological mechanisms behind this association are complex but likely involve inflammation and oxidative stress. High sugar intake has been shown to promote chronic inflammation and increase the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), both of which can damage cellular components, including DNA. Over time, this damage can lead to epigenetic changes that accelerate aging.

The Role of Essential Nutrients in Epigenetic Aging

On the flip side, the study found that higher intakes of essential nutrients, particularly those known to support epigenetic health, were associated with a younger epigenetic age. For instance, the Epigenetic Nutrient Index (ENI), which scores nutrient intakes based on their potential to support DNA maintenance and repair, was inversely associated with GrimAge2. Each unit increase in the ENI score was associated with a 0.17-year decrease in epigenetic age.

This finding is significant because it suggests that diet can play a protective role against the epigenetic changes that drive aging. Nutrients like folate, vitamin B12, and polyphenols, which are abundant in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, are known to support DNA methylation and other epigenetic processes. By ensuring adequate intake of these nutrients, it may be possible to slow down the biological aging process and reduce the risk of age-related diseases.

Diet Quality and Epigenetic Aging

The study also evaluated diet quality using the Alternate Mediterranean Diet (aMED) and the Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI)–2010. Both indices were designed to reflect adherence to dietary patterns associated with reduced risk of chronic diseases. The researchers found that higher scores on both the aMED and AHEI-2010 were associated with a younger epigenetic age. Specifically, each unit increase in the aMED score was associated with a 0.41-year decrease in GrimAge2, while each unit increase in the AHEI-2010 score was associated with a 0.05-year decrease in epigenetic age.

These findings underscore the importance of overall diet quality in promoting healthy aging. The Mediterranean diet, in particular, is rich in antioxidants, anti-inflammatory compounds, and healthy fats, all of which have been shown to support cellular health and reduce the risk of chronic diseases. By following a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, and healthy fats like olive oil, individuals may be able to slow down the epigenetic changes that contribute to aging.

Implications for Public Health and Nutrition Guidelines

The results of this study have important implications for public health and nutrition guidelines. First, they highlight the potential role of diet in modulating epigenetic aging, suggesting that dietary interventions could be an effective strategy for promoting healthy aging. Reducing added sugar intake and increasing the intake of essential, pro-epigenetic nutrients could be particularly beneficial.

Moreover, the findings support the idea that existing dietary guidelines, such as those promoting the Mediterranean diet or other plant-based diets, are aligned with the goal of slowing epigenetic aging. However, the study also raises questions about whether current guidelines adequately address the specific nutrient needs for optimal epigenetic health. For example, should there be more emphasis on specific nutrients like folate or vitamin B12 in the context of aging? Should sugar intake recommendations be even stricter, given its potential impact on epigenetic aging?

Limitations and Future Research

While the study provides valuable insights, it also has limitations that should be considered. First, the cross-sectional design means that causality cannot be established. It's unclear whether the observed associations between diet and epigenetic aging are due to the diet itself or other confounding factors. Longitudinal studies are needed to confirm these findings and establish causal relationships.

Second, the study focused on a specific cohort of midlife Black and White women, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Future research should explore whether these associations hold true in other demographic groups, including men, younger individuals, and people from different ethnic backgrounds.

Finally, while the GrimAge2 clock is a powerful tool for measuring biological age, it's not the only epigenetic clock available. Other clocks, such as the PhenoAge or Hannum clocks, may provide different insights into the relationship between diet and epigenetic aging. Future studies could compare these different clocks to determine which is most predictive of health outcomes and how they relate to diet.

Conclusion: Diet as a Key Modulator of Epigenetic Aging

The study of dietary patterns, nutrient intake, and their association with epigenetic aging is a rapidly evolving field with significant implications for public health. The findings discussed in this blog post suggest that diet plays a crucial role in modulating epigenetic aging, with higher intakes of essential nutrients and adherence to healthy dietary patterns associated with a younger biological age. Conversely, higher added sugar intake appears to accelerate epigenetic aging, potentially increasing the risk of age-related diseases.

These insights reinforce the importance of promoting healthy eating habits, particularly in midlife, when the effects of diet on aging may be most pronounced. As research in this area continues to grow, it may lead to new dietary guidelines and interventions specifically designed to support epigenetic health and promote longevity. For now, the evidence suggests that a diet rich in essential nutrients and low in added sugars is not only good for your waistline but also for your biological age.

Practical Tips for Slowing Down Epigenetic Aging Through Diet

Given the findings of this study, here are some practical dietary tips that could help slow down epigenetic aging:

Limit Added Sugar Intake: Try to minimize your consumption of added sugars by avoiding sugary drinks, sweets, and processed foods. Instead, satisfy your sweet tooth with natural sugars found in fruits.

Follow a Mediterranean Diet: Incorporate more elements of the Mediterranean diet into your meals. Focus on fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, and healthy fats like olive oil. Include fish and seafood as your primary sources of protein.

Boost Your Intake of Pro-Epigenetic Nutrients: Ensure you’re getting enough nutrients that support DNA maintenance and repair. Foods rich in folate, vitamin B12, and polyphenols, such as leafy greens, berries, and whole grains, are excellent choices.

Increase Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Foods: Include foods high in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds, such as berries, turmeric, ginger, and green tea, in your daily diet. These foods can help reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, which

Faqs

Q1: Are healthy dietary patterns associated with older epigenetic age?

A1: No, healthy dietary patterns are actually associated with a younger epigenetic age. Measures of healthy diets, such as those reflected by aMED (Mediterranean Diet), AHEI-2010 (Alternative Healthy Eating Index), and high intakes of nutrients linked to epigenetics (ENI), were found to be associated with a younger epigenetic age. Conversely, a higher intake of added sugar was associated with an older epigenetic age.

Q2: What is a good diet for balancing vitamins, proteins, and other nutrients in the body?

A2: A balanced diet should include a variety of foods such as whole fruits, vegetables, lean proteins (including seafood, lean meats, poultry, eggs, legumes, soy products, nuts, and seeds), whole grains, and plenty of water. This combination ensures that your body receives a good balance of vitamins, proteins, and other essential nutrients.

Q3: Are healthier diets associated with decelerated epigenetic aging?

A3: Yes, healthier diets are associated with decelerated epigenetic aging. For each unit increase in healthy diet scores (aMED, AHEI-2010, ENI), there was a corresponding decrease in epigenetic aging, indicating that these healthier diets contribute to a slower rate of aging at the epigenetic level.

Q4: Does nutrient intake affect epigenetic health?

A4: Yes, nutrient intake does affect epigenetic health. The study findings suggest that optimizing nutrient intake while reducing added sugar is crucial for maintaining good epigenetic health. Nutrients play important roles in DNA replication, maintenance, and repair, and also act as antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents, all of which contribute to healthy epigenetic aging.

Journal Reference

Chiu, D. T., Hamlat, E. J., Zhang, J., Epel, E. S., & Laraia, B. A. (2024). Essential Nutrients, Added Sugar Intake, and Epigenetic Age in Midlife Black and White Women: NIMHD Social Epigenomics Program. JAMA Network open, 7(7), e2422749. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.22749

Image credit:https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1169168/fonc-13-1169168-HTML/image_m/fonc-13-1169168-g003

Related:

https://healthnewstrend.com/fuel-your-health-the-power-of-metabolic-flexibility

https://healthnewstrend.com/the-role-of-diet-in-bone-health-the-dangers-of-rapid-weight-loss

Disclaimer

The information on this website is for informational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.