Is saturated fat bad for your heart? Debunking the Myths About Saturated Fats and Heart Health

Explore the complex relationship between saturated fatty acids (SFA) and heart health. Discover the latest research, debunk common myths, and learn practical tips for reducing SFA intake while maintaining a healthy diet.

DR T S DIDWAL MD

9/28/202412 min read

The relationship between saturated fatty acids (SFA) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains a complex and controversial topic. While decades of research have linked high SFA intake to increased CVD risk, recent studies have challenged this notion. According to research published in the Journal of Clinical Lipidology, the primary mechanism by which SFA is thought to increase CVD risk is through raising LDL cholesterol levels. However, the impact of SFA on cardiovascular health is multifaceted, involving factors like inflammation, cardiac rhythm, and blood clotting. Observational studies and randomized controlled trials provide evidence supporting the link between SFA and CVD, but the complexity of dietary patterns and the limitations of these studies make definitive conclusions challenging. Current dietary guidelines generally recommend limiting SFA intake, but the specific recommendations and the best replacements for SFA vary. Navigating the controversy requires considering the totality of evidence, recognizing the limitations of research, and consulting with healthcare professionals for personalized advice. Ultimately, a balanced diet rich in whole foods, with a focus on unsaturated fats, is crucial for promoting cardiovascular health.

Key points

Saturated fatty acids (SFA) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) have a complex relationship.

The primary mechanism by which SFA is thought to increase CVD risk is through raising LDL cholesterol levels.

Observational studies and randomized controlled trials provide evidence supporting the link between SFA and CVD, but the complexity of dietary patterns and the limitations of these studies make definitive conclusions challenging.

Current dietary guidelines generally recommend limiting SFA intake, but the specific recommendations and the best replacements for SFA vary.

The impact of SFA on cardiovascular health is multifaceted, involving factors like inflammation, cardiac rhythm, and blood clotting.

Navigating the controversy requires considering the totality of evidence, recognizing the limitations of research, and consulting with healthcare professionals for personalized advice.

A balanced diet rich in whole foods, with a focus on unsaturated fats, is crucial for promoting cardiovascular health.

Saturated Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease Risk

The relationship between dietary saturated fatty acids (SFA) and cardiovascular health has been a topic of intense scientific scrutiny and public health debate for decades. While conventional wisdom has long held that a diet high in saturated fats contributes to an increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), recent reviews have sparked controversy by questioning this long-standing belief. This blog post aims to delve into the complex world of saturated fats and heart health, examining the current evidence, highlighting areas of uncertainty, and providing a balanced perspective on dietary recommendations.

Understanding Saturated Fatty Acids

Saturated fatty acids (SFA) are a type of dietary fat characterized by their chemical structure, which contains no double bonds between carbon atoms. This saturation with hydrogen atoms gives them a solid consistency at room temperature. Common sources of SFA in the diet include animal-based foods such as meat, dairy products, and certain tropical oils like coconut and palm oil.

The link between SFA and heart disease first gained prominence in the 1950s and 1960s, largely due to the work of American physiologist Ancel Keys. His Seven Countries Study, which examined the relationship between dietary patterns and cardiovascular disease across different populations, suggested a strong correlation between SFA intake and heart disease rates. This research, along with subsequent studies, formed the foundation for decades of dietary advice recommending the limitation of saturated fat consumption.

However, it's important to note that our understanding of nutrition and its impact on health is continually evolving. While the association between SFA and cardiovascular risk has been a cornerstone of dietary guidance for many years, recent research has prompted a reexamination of this relationship, leading to the current debate in the scientific community.

The LDL-Cholesterol Connection

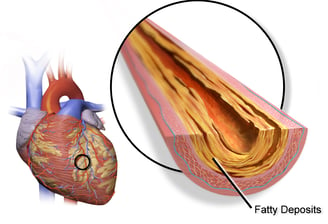

One of the primary mechanisms by which saturated fatty acids are thought to increase cardiovascular risk is through their effect on blood cholesterol levels, particularly low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). LDL-C, often referred to as "bad" cholesterol, plays a crucial role in the development of atherosclerosis, the buildup of plaque in artery walls that can lead to heart attacks and strokes.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that diets high in SFA tend to raise LDL-C levels in the blood. This effect is thought to occur through several mechanisms:

Increased cholesterol synthesis: SFA can stimulate the liver to produce more cholesterol.

Reduced LDL receptor activity: SFA may decrease the number or activity of LDL receptors, which are responsible for removing LDL particles from the bloodstream.

Changes in LDL particle size and number: Some research suggests that SFA intake can lead to an increase in small, dense LDL particles, which are considered more atherogenic than larger, more buoyant LDL particles.

The relationship between elevated LDL-C levels and increased ASCVD risk is one of the most well-established concepts in cardiovascular medicine. Numerous observational studies, genetic analyses, and clinical trials have consistently shown that higher LDL-C levels are associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular events. Moreover, interventions that lower LDL-C, such as statin therapy, have been shown to reduce ASCVD risk in both primary and secondary prevention settings. However, it's important to note that the impact of dietary SFA on cardiovascular health is not solely mediated through LDL-C. While LDL-C is a significant factor, the relationship between SFA intake and ASCVD risk is complex and multifaceted, involving various other physiological pathways that we will explore in later sections of this blog post.

Understanding the LDL-C connection provides a foundation for comprehending the potential risks associated with high SFA intake. However, as we'll see, the story doesn't end here. The interplay between diet, lipid metabolism, and cardiovascular health is intricate, and ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of these relationships.

Observational Studies: What Do They Tell Us?

Observational studies have played a crucial role in shaping our understanding of the relationship between saturated fatty acid intake and cardiovascular disease risk. These studies, including prospective cohort and case-control studies, provide valuable insights into long-term dietary patterns and health outcomes in large populations.

Several major observational studies have contributed significantly to the body of evidence:

The Nurses' Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study: These large, long-running cohort studies have consistently found associations between higher SFA intake and increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD).

The PURE (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology) study: This global study of dietary patterns in 18 countries found no significant association between total fat or saturated fat intake and cardiovascular disease or mortality. However, it did find that replacing saturated fat with unsaturated fat was associated with lower risk.

The EPIC (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition) study: This large European cohort study found that higher SFA intake was associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk, particularly when replacing SFA with polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Randomized Controlled Trials: The Gold Standard

While observational studies provide valuable insights, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the gold standard for establishing causal relationships in medical research. However, conducting long-term dietary intervention trials to assess hard cardiovascular endpoints is challenging, expensive, and relatively rare.

Some key RCTs that have examined the relationship between SFA intake and cardiovascular outcomes include:

The Oslo Diet-Heart Study (1966-1992): This pioneering study found that replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats reduced cardiovascular events and mortality.

The Finnish Mental Hospital Study (1959-1971): This institutional-based trial showed a reduction in coronary heart disease events when saturated fats were replaced with polyunsaturated fats.

The Women's Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial (1993-2005): This large-scale trial found no significant effect of a low-fat diet (which included reduced SFA) on cardiovascular outcomes. However, the achieved reduction in SFA intake was modest, which may have limited the study's ability to detect an effect.

The PREDIMED trial (2003-2011): While not specifically focused on SFA, this study found that Mediterranean diets supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts, both lower in SFA than typical Western diets, reduced cardiovascular events compared to a control diet.

Beyond LDL: Other Potential Mechanisms

While the effect of saturated fatty acids on LDL cholesterol levels is well-established, research has uncovered several other potential mechanisms by which SFA intake might influence cardiovascular health:

Inflammation: Some studies suggest that high SFA intake may promote systemic inflammation, a key factor in the development and progression of atherosclerosis. However, the evidence is mixed, with some studies showing pro-inflammatory effects and others showing no significant impact.

Cardiac rhythm: There is some evidence that high SFA intake might affect heart rhythm and increase the risk of arrhythmias. This could potentially contribute to sudden cardiac death, although more research is needed to confirm this link.

Hemostasis and blood clotting: Some studies have found that diets high in SFA may increase factors involved in blood clotting, such as factor VII coagulant activity. This could potentially increase the risk of thrombotic events, although the clinical significance of these findings remains uncertain.

Apolipoprotein CIII production: SFA intake has been shown to increase the production of apolipoprotein CIII, a protein that inhibits the clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Higher levels of apoC-III have been associated with increased cardiovascular risk.

5. HDL function: While SFA intake often raises HDL cholesterol levels (traditionally considered "good" cholesterol), some research suggests it may impair HDL function. The quality and functionality of HDL particles may be more important than their quantity in determining cardiovascular risk.

6. Insulin resistance: Some studies suggest that high SFA intake, particularly from certain sources, may contribute to insulin resistance, a key factor in the development of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, both of which increase cardiovascular risk.

It's important to note that while these mechanisms are biologically plausible and supported by some evidence, their relative importance and overall impact on cardiovascular risk remain areas of active research. The complexity of these interrelated pathways underscores the challenges in fully understanding the relationship between SFA intake and cardiovascular health.

Replacing SFA: What Are the Alternatives?

When considering recommendations to reduce saturated fatty acid intake, it's crucial to consider what nutrients will replace SFA in the diet. The health effects of reducing SFA may depend largely on what replaces it:

1. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs):

Replacing SFA with PUFAs, particularly omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids, has been consistently associated with reduced cardiovascular risk in both observational studies and randomized trials.

PUFAs have been shown to lower LDL cholesterol, reduce inflammation, and improve insulin sensitivity.

Sources include vegetable oils (such as soybean, corn, and sunflower oil), fatty fish, nuts, and seeds.

2. Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFAs):

Replacing SFA with MUFAs has also been associated with cardiovascular benefits, although the evidence is not as strong as for PUFAs.

MUFAs may help lower LDL cholesterol and have beneficial effects on insulin sensitivity.

Sources include olive oil, avocados, nuts, and seeds.

3. Carbohydrates:

The effects of replacing SFA with carbohydrates depend largely on the quality of the carbohydrates.

Replacing SFA with refined carbohydrates and added sugars may not provide cardiovascular benefits and could potentially increase risk.

However, replacing SFA with whole grains and other high-quality, fiber-rich carbohydrates may have beneficial effects on cardiovascular health.

4. Protein:

The effects of replacing SFA with protein are less well-studied and may depend on the protein source.

Plant-based protein sources (such as legumes and nuts) may offer cardiovascular benefits when used to replace SFA.

The effects of replacing SFA with animal protein are less clear and may depend on the specific type of meat and its preparation method.

Current Dietary Guidelines and Recommendations

Based on the current body of evidence, most major health organizations continue to recommend limiting saturated fat intake as part of a heart-healthy diet. Here's an overview of current guidelines:

General Population:

The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends limiting saturated fat intake to less than 10% of total daily calories for the general healthy population.

The 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans also suggest limiting saturated fat to less than 10% of calories per day.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends reducing saturated fat intake to less than 10% of total energy intake and replacing it with unsaturated fats.

High-Risk Groups:

For individuals with hypercholesterolemia or established cardiovascular disease, the AHA recommends further reducing saturated fat intake to 5-6% of total daily calories.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) guidelines recommend a saturated fat intake of less than 7% of total energy for high-risk individuals.

Type of Replacement:

Most guidelines emphasize replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats, particularly polyunsaturated fats, rather than with refined carbohydrates or added sugars.

Food-Based Recommendations:

Many guidelines are moving towards food-based recommendations rather than focusing solely on nutrients. This approach encourages the consumption of whole foods like fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats while limiting processed foods high in saturated fats.

It's important to note that these guidelines are based on the best available evidence but are subject to change as new research emerges. They are intended as general guidance and may need to be adapted to individual circumstances under the supervision of healthcare professionals.

Navigating the Controversy

The relationship between saturated fat intake and cardiovascular health remains a topic of debate in both scientific and public spheres. Several factors contribute to this ongoing controversy:

Conflicting Study Results:

While many studies support the link between high SFA intake and increased cardiovascular risk, some recent studies have found no significant association.

These conflicting results can be attributed to differences in study design, population characteristics, dietary assessment methods, and the specific outcomes measured.

Complexity of Dietary Patterns:

Isolating the effects of a single nutrient like saturated fat is challenging because people consume diets, not isolated nutrients.The overall dietary pattern and lifestyle factors may be more important than any single nutrient in determining cardiovascular risk.

Food Source and Fatty Acid Composition:

Not all saturated fats are created equal. The health effects may vary depending on the food source and the specific types of saturated fatty acids involved.

For example, some studies suggest that dairy fat may have a neutral or even beneficial effect on cardiovascular health, despite its high saturated fat content.

Industry Influence:

The food industry, particularly sectors that produce high-SFA foods, has a vested interest in the outcomes of nutrition research and dietary recommendations.

Some critics argue that industry funding and influence may bias research findings or public messaging about saturated fats.

Evolving Understanding of Lipid Metabolism:

Our understanding of lipid metabolism and its relationship to cardiovascular disease is continually evolving.

New research on topics like LDL particle size, apolipoprotein B, and HDL functionality is adding nuance to the traditional view of cholesterol and heart disease risk.

Media Representation:

Media coverage of nutrition research often oversimplifies complex findings, leading to public confusion and skepticism about dietary advice.

To navigate this controversy, it's important to:

Consider the totality of evidence rather than focusing on single studies

personalized dietary advice

Practical Implications: Translating Science to the Plate

While the scientific debate continues, individuals and healthcare providers need practical strategies for implementing heart-healthy diets. Here are some approaches for reducing saturated fat intake and improving overall dietary quality:

Focus on Whole Foods:

Emphasize fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds in the diet.

Choose lean proteins, including plant-based options, fish, and poultry.

Choose Healthier Cooking Oils:

Replace oils high in saturated fats (like coconut oil or palm oil) with those rich in unsaturated fats (like olive oil, canola oil, or avocado oil).

Limit Processed and Fast Foods:

Many processed and fast foods are high in saturated fats. Reducing consumption of these foods can significantly lower SFA intake.

Read Nutrition Labels:

Be aware of the saturated fat content in packaged foods and choose lower-fat options when available.

5. Modify Dairy Intake:

- Consider switching to low-fat or fat-free dairy products if consuming full-fat versions.

Explore plant-based dairy alternatives, keeping in mind their overall nutritional profile.

Choose Lean Meats and Practice Portion Control:

When consuming meat, choose leaner cuts and practice portion control.

Saturated Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Examining the Evidence

Conclusion and Future Directions

The relationship between saturated fatty acid intake and cardiovascular disease risk remains a complex and evolving area of nutrition science. While the weight of evidence continues to support limiting SFA intake as part of a heart-healthy diet, particularly when replaced with unsaturated fats, the debate is far from settled.

Key points to remember:

Current guidelines recommend limiting SFA intake to less than 10% of total daily calories for the general population, with further reductions for high-risk individuals.

Replacing SFA with polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fats appears to offer the most consistent cardiovascular benefits.

The overall dietary pattern and lifestyle factors are likely more important than any single nutrient in determining cardiovascular risk.

Individual responses to dietary fats may vary, and personalized approaches to nutrition are increasingly recognized as important.

Future research directions may include:

More long-term randomized controlled trials examining the effects of different dietary patterns on cardiovascular outcomes.

Studies on the effects of specific types of saturated fatty acids from different food sources.

Investigation of gene-diet interactions that may influence individual responses to saturated fat intake.

As our understanding of nutrition and cardiovascular health continues to evolve, it's crucial for both the public and healthcare providers to stay informed about the latest research. While we may not have all the answers, the current evidence supports the importance of a balanced diet rich in whole foods, with a focus on unsaturated fats, as a key component of cardiovascular disease prevention.Ultimately, heart health is influenced by a combination of dietary factors, physical activity, stress management, and other lifestyle choices. By taking a holistic approach to cardiovascular health and staying informed about the latest nutritional science, we can make choices that promote long-term wellbeing and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Related Articles

1.Cholesterol and Heart Health: What the Science Says

2.Early Detection of Heart Disease in Women: 3 Key Biomarkers

Journal References

Maki, K. C., Dicklin, M. R., & Kirkpatrick, C. F. (2021). Saturated fats and cardiovascular health: Current evidence and controversies. Journal of clinical lipidology, 15(6), 765–772. According

Feingold, K. R. (2024, March 31). The Effect of Diet on Cardiovascular Disease and Lipid and Lipoprotein Levels. Endotext - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570127/

Image credit: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d1/Blausen_0257_CoronaryArtery_Plaque.png

Disclaimer

The information on this website is for informational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health care provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.